I heard the sad news of author Pat Conroy’s death last Friday, March 4, on NPR. Those who do not recognize his name probably still know his finest novels: The Prince of Tides, The Great Santini, and The Lords of Discipline. He was taken by pancreatic cancer only four weeks after diagnosis, at age 70.

Conroy was far and away my favorite author. He was the poet laureate of the South, a storyteller supreme, inspired by both the breathtaking beauty of the South Carolina Lowcountry and his own dysfunctional family. His writing was lyrical, painfully personal and poignant. For thirty years I felt like I knew the man, or should have known him. When I read the The Prince of Tides in 1986, I silently surrendered my own writing ambitions because in him I found an author who said everything I hoped to say, only vastly better.

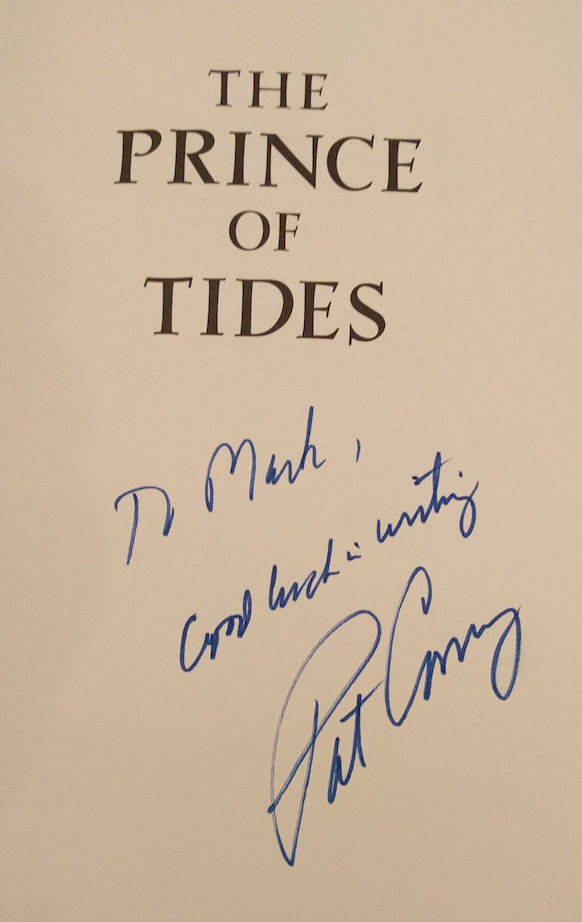

I met Pat Conroy, once, at a book signing in Northern Virginia shortly after the publication of Beach Music. I was with my mother, also a fan, who had sent me The Prince of Tides a few years earlier and insisted I drop everything to read it. She and I waited in line half an hour before Conroy came into view. I studied him: prematurely white hair, ruddy Irish face, witty smile, compassionate eyes. He was about the age I am today. Everyone in line was a bumbling gawker, me included, and I could see that Conroy knew how to handle us. As each adoring reader stepped forward, before they could say a word, he asked the same question: “Do you live around here?” My mother, who was in front of me, gushed that yes, yes, she did live in the area. And by then her book was signed and she was whisked along. Smooth. When Conroy asked me if I lived around there, I ignored the question and told him I hoped to write a novel one day. His eyes twinkled (he had heard that a few times, I suspect), and this is what I got:

Before I moved on, I asked him if his new book, Beach Music, was better than The Prince of Tides. He smiled at me. “No.”

Fast forward twenty years.

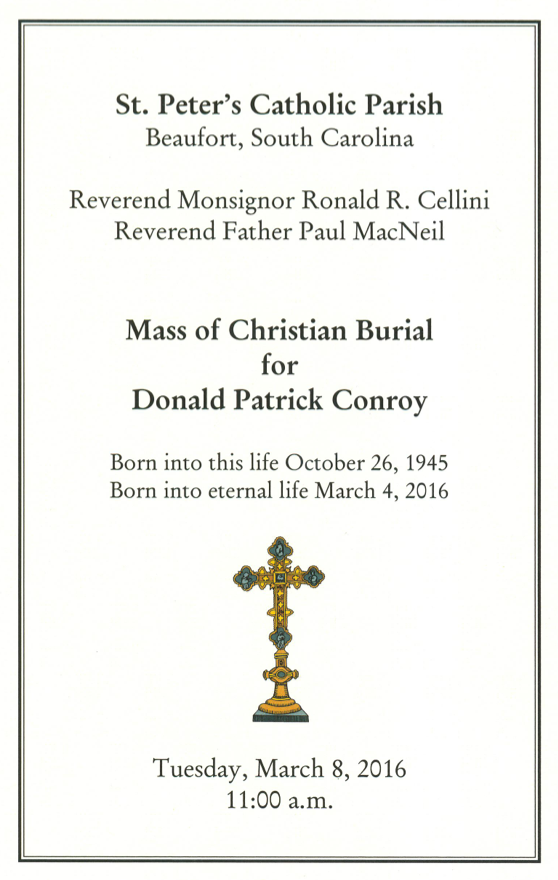

On Monday I saw an article online in the Beaufort Gazette with the details of Conroy’s funeral, which was to be the following day, March 8, and open to the public. I knew I would I go. I wanted to be present at the moment when this life was honored by those who knew him best.

I drove in darkness for three hours on Monday night, stopping in a small town an hour from Beaufort, his hometown. The next morning I rose early and followed Highway 21 eastward. The early fog lifted and the Lowcountry was revealed: still, mirror-like marshes and stately blue herons. I was in Conroy country.

I reached St Peter’s Catholic Church more than two hours before the services were scheduled to start. I was worried the church might already be crowded, but in fact only a few early birds gathered in the nathex. A small group welcomed me into their circle, and I immediately confessed that I was neither friend nor family, just a fan who had driven in from Charlotte. They were warm and friendly, moved that I had driven so far. Stan Lefco, the first to greet me, told me that he and the two women with him had driven from Atlanta the previous day. Each of them were children of Holocaust survivors.

Stan’s wife Jane had been Conroy’s financial advisor and bookkeeper, and had paid his bills for years. Stan told me that Pat called almost every day, and when Jane died in 2008, at 58, Pat had delivered her eulogy. What a eulogy it must have been, but Stan told me he recalled not one word of it, not on that grievous day. He still gets mail for Pat, and for Jane.

Stan’s traveling companions were Martha and Sarah Popowski. Their mother Paula, who is 94, is a Holocaust survivor who was sent with her sister to Treblinka in 1942. Paula’s mother had fashioned gold coins into buttons and sewn them onto her dress, and throughout the war she seldom removed it. The gold coins would eventually allow Paula and her sister to escape to freedom. Standing before me in this Catholic church were her two daughters, whose very existence is a miracle and a testament to a mother’s love and ingenuity.

Martha met Pat in 1985. She was watching the Peachtree 10K in Atlanta on July 4th. A runner had shouted “Hey, Santini!” and Martha realized she was standing close to Pat Conroy and his father, Donald, the Great Santini. She made her way over to him and struck up a conversation. As a child of immigrants, she had been moved by Pat’s novel The Water is Wide, inspired by his year of teaching profoundly impoverished children in a two room schoolhouse on Daufuskie Island. Pat in turn was fascinated by her family’s tale of the Holocaust. A chance encounter at the Peachtree road race led to dinners and friendship, and later Pat would model his mysterious Beach Music character, The Lady of Coins, after Martha and Sarah’s mother.

Martha told me that Pat called her regularly over a thirty year period. She never knew where or how to find him, but he could always find her, and he did. He had a way of keeping in touch.

I followed Stan, Martha and Sarah into the church and we sat immediately behind the reserved pews in the transept. At first I protested: someone with my thin connection to Pat should be sitting in a folding chair in the back. No, they insisted, I would sit with them.

There was still an hour to wait before the services began. A woman slid into the pew next to me on the other side and we immediately said hello. Her name was Susan Julavits. I began, again, with my confession of having no real tie to Pat. She and her husband knew him well. They had dined with Pat at his favorite restaurant in Beaufort, Griffin Market, and he had regaled them with tales of his high school antics with Bernie Schein. Susan’s daughter, Heidi Julavits, is a successful author in New York. Pat loved her writing — had called more than once to say so — and had attended a Luncheon with Authors event at the University of South Carolina where she was featured. His support for other authors, Susan told me, was unprecedented.

Sitting in the pew between the children of the Holocaust survivors and the mother of an author, a sense of belonging came over me. Here were people who knew Pat, in whose lives he had a been a regular presence. And they were so warm and kind to me, respecting my respect for him. It was in this moment that I realized he had become simply “Pat” in all my conversations about him over the past hour.

The organ began to play and more and more people filed into the nave. Half the pews on one side were reserved for the Citadel, Pat’s alma mater and the target of his skewering The Lords of Discipline. After decades of animosity, the Citadel had invited Pat to give the commencement address in 2001. He accepted, and in his remarks invited every graduate of that year to attend his funeral, whenever it might be. They need only say “I wear the ring” to gain admission to the church on that day. And indeed row after row of 2001 graduates filed in, along with a strong contingent of white haired men from Pat’s class of 1967. The current President of the Citadel, Lieutenant General John Rosa ’73, was resplendent in his Class A uniform.

When the pews were filled, a soloist sang the mournful Scottish folk song The Water is Wide,

The water is wide, I can’t cross o’er

And neither I have wings to fly

Give me a boat that can carry two

And both shall row — my love and I.

The song is meaningful to fans of Pat Conroy: it’s the title of his first major novel. It’s also a song I know well. In 2002, dear friends lost their first child as they drove to the hospital for delivery. The baby’s heartbeat stopped shortly after the mother’s contractions began. We were devastated and wholly unable to comfort them. After a few days I made a CD for them with a dozen different renditions of this single song.

As I listened to the slow, melancholy lyrics, my face felt swollen and tears collected in my eyes. I turned to look at Pat’s widow, Cassandra King, who was seated in the first row of the nave. She was petite but frail, crushed by grief. I looked away. I had no right to be part of that moment.

Before the service began, Judge Alex Sanders walked to the pulpit. He is a portrait of the Lowcountry gentleman statesman, slender and silver haired. Judge Sanders had been the President of the College of Charleston, the Chief Judge of the South Carolina Court of Appeals, and a former member of both the state House and Senate. He had the tall order of delivering a eulogy for Pat Conroy. How does one weave together words in a manner befitting one of the greatest writers of a generation?

He did it by quoting at length from The Prince of Tides, the same passage quoted by the New York Times in its March 5 tribute:

“To describe our growing up in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, I would have to take you to the marsh on a spring day, flush the great blue heron from its silent occupation. Scatter marsh hens as we sink to our knees in mud, open you an oyster with a pocketknife and feed it to you from the shell and say, ‘There. That taste. That’s the taste of my childhood.’ I would say, ‘Breathe deeply,’ and you would breathe and remember that smell for the rest of your life, the bold, fecund aroma of the tidal marsh, exquisite and sensual, the smell of the South in heat, a smell like new milk, semen and spilled wine, all perfumed with seawater.”

Only the Judge left out the word “semen.” For decorum, I suppose, or out of respect for the Catholic church. I believe Pat would have noticed the omission and frowned.

The service was traditional, adoring and uplifting. Through it all, Pat’s draped coffin rested before the altar. Inside that coffin was the great poet and storyteller, his personal torment now ended and his pen still.

Thank you, Pat, for enriching my life and the lives of those who knew you, and the lives of millions of others who know you only by your words.

_w200_h/Campfire%20Tales%20Cover%20Art(1)_09140500.jpg)